How to Convert your Freshwater Boat for Saltwater Use

Some people say that freshwater boats will die in saltwater: a boat that 'has seen salt' won't sell as quickly - myths if you ask me. If you're planning to move your freshwater boat to coastal waters, you want facts, not myths. So in this article I'll give you a step by step plan - based on facts, not emotions.

How to convert a freshwater boat to saltwater? You have to install several systems to increase your boat's resistance to salt corrosion. You may install a closed cooling system, a Mercathode system, apply anti-foul paint, and use stainless fasteners. Sometimes you'd even want to change the engine. Most importantly, you need to change your maintenance routine.

Converting your boat comes at a cost, but it can be done - and if you're mechanically inclined, you can do much of the work yourself. In this post we take a look at all different aspects of the conversion. It's a cool process, in which you get to electrify your boat. By the way, it's also a good idea to paint your trailer.

On this page:

Details of the Conversion

Let's start by getting something clear: there is no perfect solution to saltwater. Everything that comes into contact with salt will corrode eventually. But that's no reason to get anxious. There are plenty of solutions that will dramatically reduce or slow down the effects of salt. And if you implement them before going in, it will save you a lot of money.

Please note that not all steps are necessary. It depends on your current setup and the amount of money you're willing to spend (and the amount of maintenance you're prepared to do in the future).

Here are the steps for a full saltwater conversion:

- evaluate your current setup

- apply anti-foul bottom paint

- install a full closed cooling system ... OR:

- install a freshwater flush system

- install a Mercathode system if docked in saltwater marina

- change out your hardware and electrical system to marine-grade

- change your magnesium anodes to aluminum ones - an alternative is zinc

- change out fasteners for stainless steel ones

- replace your bilge pump with a saltwater one

- get yourself an aluminum trailer (or treat your steel one)

- maintenance, maintenance, maintenance

Evaluating Your Current Setup

What happens if you bring a freshwater boat to a saltwater fight? Nothing, really. As long as you know what you've got and how to take care of it. Some things to consider:

- What engine do I have? I'll explain more in-depth on engines later, but for now: I/O or Sterndrive engines are a nuisance. Outboard is fine, but require extra maintenance. An inboard engine with full closed cooling system is your number one option.

- What materials are my anodes made of? - If you currently have magnesium anodes, you should try to switch them out for aluminum (or zinc) ones. They offer better protection in saltwater.

- What material is my hull made of, and is it coated? - If you're planning on going out on open sea, you should make sure your hull is strong enough and has a keel. If you have an aluminum hull, that's not the best for ocean use. Fiberglass is great.

- What quality is your hardware and electrical system? - Automotive-grade hardware is very popular for inland boats. Unfortunately, it isn't any good in saltwater, so I definitely recommend changing it out.

The Effects of Saltwater

- engine wear - especially with raw water cooling

- hull fouling

- galvanic corrosion

The most important effect of saltwater is galvanic corrosion (explanation below). This will slowly eat away any aluminum and steel parts. The part that suffers most (by far) is your trailer. Next one is your engine.

If saltwater runs through your engine, your engine will ultimately die. The number one concern when moving a boat into saltwater is managing engine corrosion. If you don't, it will reduce engine performance, until it blocks one day and doesn't work at all. So pay close attention to your engine block, exhaust, manifolds, and driver and rinse systems. If you have the money, consider upgrading (scrolls down).

The reason that saltwater is so corrosive is because it's such a great conductor (it contains lots of dissociated ions). It's not so much rust that will cause problems, but all kinds of electrolysis reactions. Galvanic corrosion is one of them.

But salt will also damage your hull if it isn't protected. If you sail on inland water you get away with a bare-hull season. In saltwater not so much. It's recommended to protect the hull by applying anti-foul bottom paint.

Another great reason to apply protective paint is hull fouling. Hull fouling, (or bottom fouling) is the growth of marine organisms on your boat - for example Barnacles and algae. It takes some effort to clean, but if you don't it will damage the material over time. Barnacles can slice through your driveshaft and gear linkage bellows.

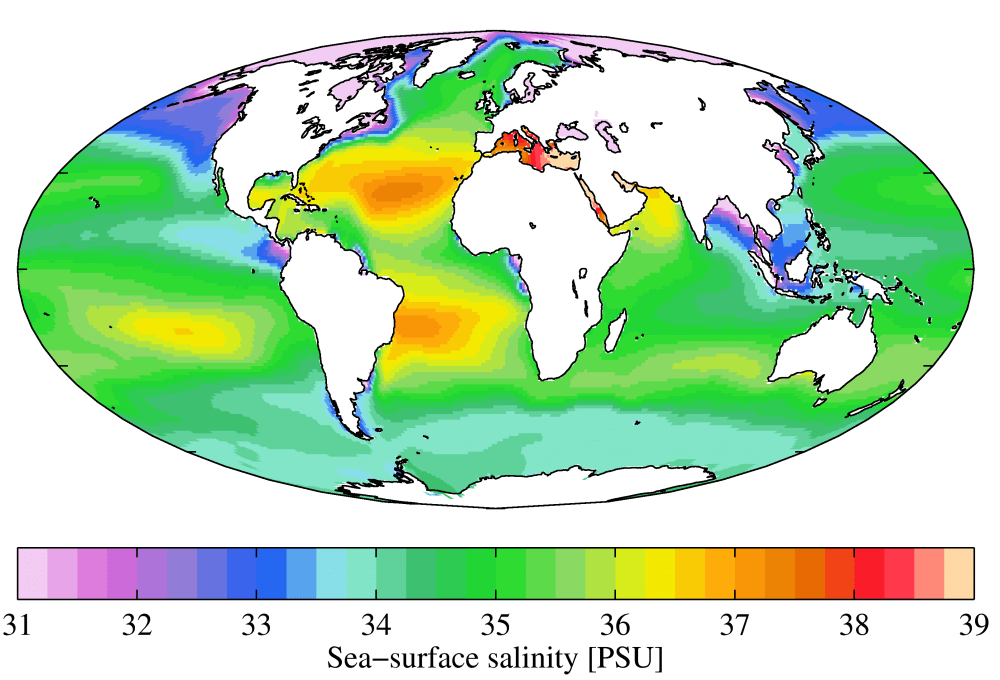

Salinity

It's important to note that the amount of salt in the water (called 'salinity') differs per region. The water in the Caribbean is far more salty than Northern waters. The Mediterranean Sea and Indian Ocean are also extremely salty. In general, places with lots of rain are less saline, as are coastal waters, where rivers add freshwater. One of the least saline seas is the Baltic, where hundreds of rivers add freshwater.

Map courtesy of Plumbago - CC BY-SA 3.0

What's galvanic corrosion?

Galvanic corrosion (also called bimetallic corrosion) is an electrochemical process in which one metal corrodes preferentially when it is in electrical contact with another, in the presence of an electrolyte

Source: Wikipedia

In plain English this means that whenever you have two metals and dip them in the ocean (the electrolyte), one of them will start to corrode. Actually, your entire boat starts to behave like a battery. That's it.

So galvanic corrosion is bad for everything that's under water. For example, most engines use an aluminum propellor on a stainless steel shaft. Alarm bells: two metals under water. In this case, the aluminum will corrode first.

How to fix galvanic corrosion? Simple: you add another metal to the mix, one that corrodes more quickly than the others. This piece of metal is called the sacrificial anode. Sacrificial because ... well, it get's sacrificed. It takes the proverbial hit, ensuring other (important) metal parts won't corrode. Make sure to change the anode once half of it is gone due to corrosion.

In some cases this process gets accelerated by adding an electrical source. This is called electrolytic corrosion (or stray current corrosion). This happens for example when there's a short in your 12V electrical system. The current leaves your boat at the bottom, into the grounded seawater. The result is very heavy metal corrosion within days or hours.

Mercathode system

Sometimes the sacrificial anode isn't enough to protect your boat. For example when the surface you want to protect is just too big. In those cases you need to take extreme measures and install a Mercathode system.

A Mercathode system is a cathodic protection system that runs a tiny electric current through your engine block and outdrive. The electric current is used to stop galvanic corrosion on metal parts that are submersed.

Do you need a Mercathode system? Generally you only need one if you dock your boat in a saltwater marina. Galvanic erosion accelerates whenever you're plugged into 120V dock power. Also, the other boats in the marina can cause acceleration.

If you trailer your boat after each trip I think getting a Mercathode is a bit of overkill.

Picking the Right Engine

The number one horror story on freshwater boats that have seen salt ... must be the engine. And it's true: the wrong kind of engine can be a disaster in saltwater. Or actually: the wrong type of cooling system.

If there's one takeaway from this article, it should be to avoid I/O engines with raw water cooling as much as possible for saltwater use.

Your best option is an inboard engine with fully closed cooling system.

What does that mean?

There are three engine types:

- Outboard: attached to the stern, can be lifted out of the water

- Inboard: fully integrated

- I/O or sterndrive: external propellor, inboard engine block (below deck)

There are three cooling systems available:

- raw water cooling system

- half closed cooling system

- full closed circuit cooling system

Outboard engines can be lifted out of the water when their not in use: this greatly reduces corrosion. They're also the most inexpensive option. They're not optimal, but they're not bad either. Maintenance is also easier than on a sterndrive engine.

Raw water cooling means the engine sucks in external water to cool itself: the same water you're in ... salt water. This will clog up the interior, reducing performance, until it ultimately blocks and dies.

Closed cooling systems have a closed loop and use their own coolant. They don't use external water, which is why they don't suffer from corrosion as much as raw water systems. There are also half closed systems that cool the exhaust manifolds and risers with external water. So they still suffer from corrosion, just not as much as a full raw water system.

The real problem lies with I/O engines that use raw water cooling (or partially: the half closed system). You can't lift them out of the water when they're not in use. The outdrive stays submerged. If you plan on docking your boat in a saltwater marina, this greatly increases corrosion on the propellor, shaft, and engine block itself.

When using a raw water system, you should plan on replacing your risers and manifolds every 3 - 6 years (on average, depending on salinity). It's not cheap at all: it may cost you up to $5,000, depending on parts availability and cost of labor. In comparison: in freshwater your manifolds could last for 10 years or more.

When your boat is permanently submerged in saltwater, you're best bet is an inboard engine with full closed cooling system. If I had an I/O engine, and the cash to spend on it, I'd probably consider upgrading my engine now.

Installing a Closed Cooling System

If you don't want to upgrade your current engine, you can also consider to install a full closed cooling system. The cost of a kit runs anywhere between $1,000 - $2,000. I hope to write an article in the near future on how to do it.

Good Saltwater Maintenance

Even if you upgrade the engine, you'll still have to maintain it. Saltwater maintenance isn't super hard, but involves a bit more work than freshwater maintenance. It can easily take you up to an hour of work after each trip. If it's less, you're probably doing too little. To summarize, it comes down to flushing, washing, hosing, and hosing some more.

Flush the engine

First of all, if you have any kind of raw water cooling system, make sure to flush the engine with freshwater for at least 10 - 15 minutes. If you want to reduce salt corrosion, you may also want to use additives or an engine flush. These inhibitors will dissolve salt and leave a protective coating that reduces future corrosion.

If you want to know what engine flush I recommend, head over to my recommended products page here.

Hose down everything

You want to hose down your boat as soon as possible - within a couple of hours if possible. If you leave it in a saltwater marina you at least want to pump out the bilge. The bilge tends to be rust sensitive, and removing the saltwater helps to slow it down a bit. Make sure to have a saltwater bilge pump.

If you trailer your boat, make sure to hose down both the boat and the trailer. Pay extra attention to your trailers tail lights, brakes, electrical connectors and axle.

Want to kill two birds with one stone? The best way to clean both the engine and the trailer is finding a freshwater ramp on your route home. Lower the trailer onto the ramp, deep enough to get to all the spots that were exposed, and run the engine for 10-15 minutes.

Once you're home I recommend still hosing down everything, just to be sure.

About that trailer

- Aluminum trailers rust less than steel frames - even if it's galvanized. If you can get a galvanized aluminum trailer, that's great. If you can't, you might consider painting the frame.

- Treat leaf springs with a thick lubricant like CorrosionX HD. Repeat the treatment every six months or so. This will make them last for years.

- Replace all fasteners and lug nuts with stainless steel ones.

- Treat all other nuts and bolts with WD-40 or Corrosion X. This covers them in an oily film, which will keep the water out. Top tip: spray your trailer just before you load the boat back on the trailer. This makes it way easier to get to all spots that are usually hard to reach. Repeat every three or four trips.

Can You Use a Freshwater Boat in Saltwater?

You can definitely use a freshwater boat in saltwater - no problem. If you plan on trailering it after each trip, you might not need to do any major upgrades or installations. But it does pay off to do good and solid maintenance.

However, sometimes people mean something completely different. When they say 'saltwater', they actually mean offshore boat. Offshore boats are not the same as saltwater boats - please don't confuse the two. Offshore boats have a different hull type, and also a keel. This makes them suitable for ocean sailing. Their hull is stronger, and the keel stabilizes them to handle larger waves.

Know your equipment. Coastal and inland boats are not offshore boats. Inland boats are not suitable for bluewater sailing. If you go sail the open seas on an inland boat, you run the risk of capsizing, or worse.

If you want to know more about the difference between freshwater and saltwater boats, I encourage you to read my previous article here.

Related Questions

How often should I replace anodes? You should replace your outboard anodes when half of the anode has corroded away. On average, this is once per year. If you need to replace your anode more often than once a year, you should get a heavier one. A magnesium anode could for example be replaced by a zinc one.

What happens to aluminum in saltwater? Aluminum doesn't rust in saltwater, but it corrodes due to galvanic corrosion. This forms a white layer on its surface. Galvanic corrosion is an electrochemical reaction where one of two metals starts to corrode away when they are in electric contact with each other. Saltwater acts as the electrolyte.

What metal is most resistant to saltwater? Stainless steel is very resistant to saltwater corrosion. Copper, brass, and bronze are as durable, but are more expensive, so less practical in use. Aluminum is less resistant to galvanic corrosion, but can be a viable option when treated. The least resistant metal is galvanized steel.

How long should you flush your outboard? You should flush your outboard engine with freshwater for at least 10 - 15 minutes after all saltwater use. You may want to add some salt remover to treat the interior of the engine block and form a protective layer as well. If you don't flush, galvanic corrosion can become a real problem.

Did you find the answer to your specific question?

👍 16 👎 0

Comments

Mercruiser Water Pumps

Really Your Blog is awesome/

Shawn Buckles

Thanks a lot for the kind words

Mercruiser Water Pumps

Thanks, Exactly i Need That.

Mercruiser Water Pumps

Really Good information Thanks For Shareing With Us.

Mercruiser Water Pumps

It’s remarkable to visit this website and reading the views of all friends concerning this paragraph, while I am also zealous of getting knowledge.

Javier Rodriguez

I am hunting for my first boat, Just reading this article open my eyes. Thanks, very instructional. I will follow you on Youtube.

Larry Weber

My First time buying a boat so Iam sure i will have plenty of questions in the near future.Thanks

Leave a comment