Points of Sail Explained (with Degrees and Diagram)

When you're new to sailing, you discover a whole new language to describe what's going on with the boat. One of the most fundamental pieces of terminology you'll learn day one in every Learn to Sail course are the points of sail.

Every direction of sailing relative to the wind has a name, and the meaning of that main is a critical piece of understanding you'll need when you're learning to sail. The main points of sail from straight upwind are beating (or "close hauled"), reaching (close, beam, and broad), and running. There is also a no-sail zone straight upwind, though this is not generally viewed as a point of sail since you can't sail there.

Upwind Sailing: Against the Wind

The physics of sailing a boat downwind is pretty simple - the wind fills the sails and pushes on them, and the boat is pulled through the water by the forces on the sails.

But how about sailing upwind? The wind is pushing against the boat after all.

While a full explanation is outside the scope here, a boat moves upwind by a combination of forces of the wind on the sails and the keel resisting that force against the water. Wind pushes against the sails with a lifting force and tips the boat, and the keel pushes back against the water and keeps the boat from side-slipping. The combined forces net out in the forward motion of the boat.

As the bow of the boat turns away from the wind, we adjust the sails to keep the forces maximized and the boat moving efficiently.

Apparent Wind is the wind as it feels on the boat, versus true wind, which is the absolute wind speed and direction over the water. Apparent wind includes the true wind and the motion of the boat added together. A bicyclist riding at 10 knots straight into a 5-knot breeze feels 15 knots of apparent wind, but riding downwind they feel only 5 knots. Sailing upwind, the boat is moving into the wind and the apparent wind increases. The opposite happens when you sail downwind.

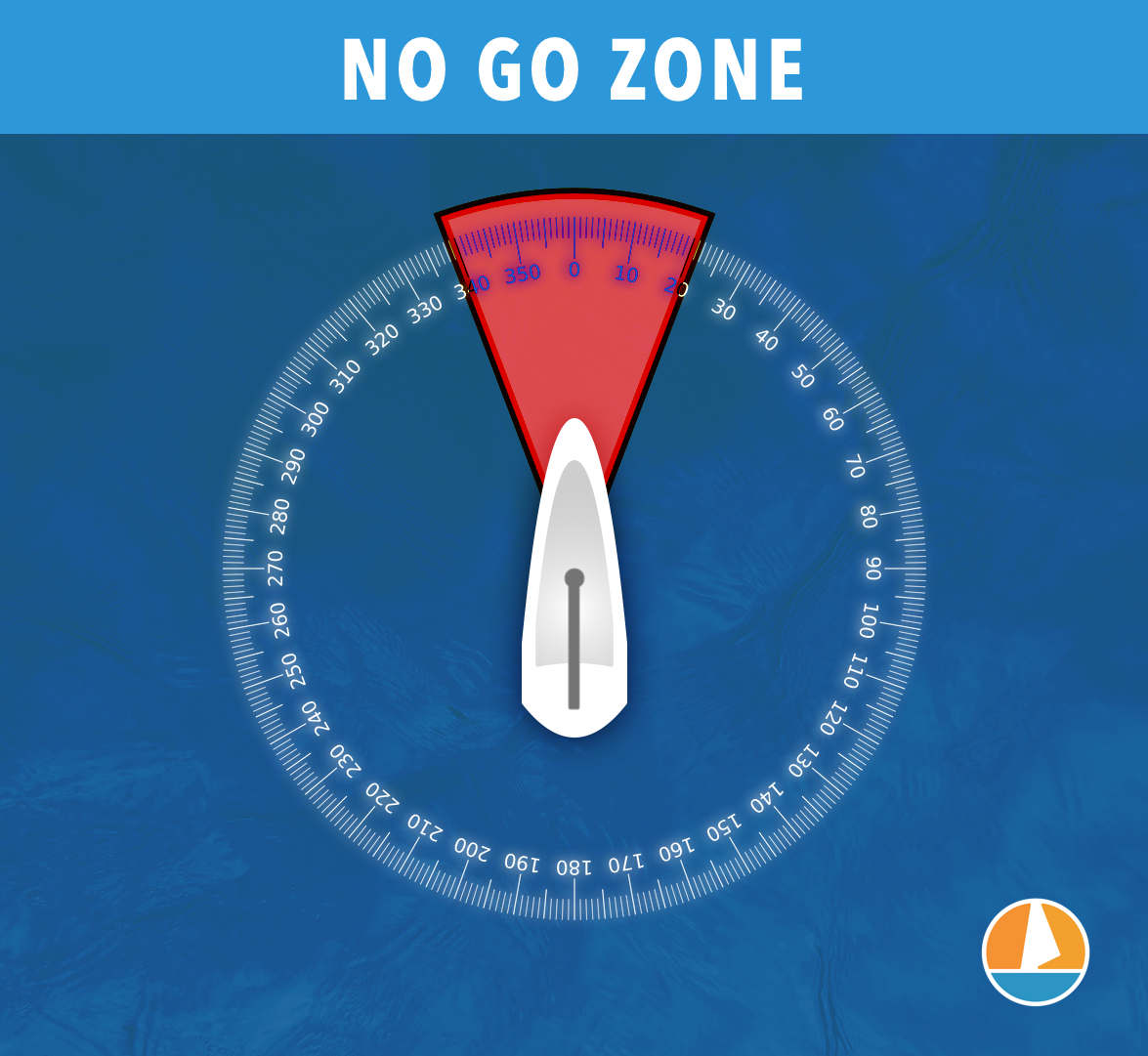

No-Sail Zone: Limit to Upwind Sailing

Sailboats can not sail straight upwind. The wind and water work against the sails and keel to propel a boat upwind, but there is a practical limit upwind beyond which a boat can not sail. Any boat trying to sail in the no-sail zone will end up in irons and lose control and drift until the bow falls far enough off the wind for the sails to fill and work again.

The exact size of the no-sail zone varies by the type of the boat and its rig, as well as how skillfully it is trimmed. A high-tech, modern racing boat with a professional crew can sail up to about 30 degrees off the wind, and an old square rigger might struggle to sail 70 degrees off the wind. A typical small boat sailed by amateur sailors will sail about 45 degrees off the wind.

Forty-five degrees off the wind makes for a ninety-degree angle cone upwind where a typical boat can not sail.

Close-Hauled: Sailing Close to the Wind

Close-hauled, also known as beating, is sailing as close to upwind as the boat can without stalling. For a typical boat, this is about forty-five degrees, though careful observation of the boats you sail on will show some variety in this number.

To sail upwind, sheet sails mostly in and bring the boom to centerline. The boat will heel as it gets on the wind, and this is the point of sail with the most tipping. The apparent wind is also highest close hauled, and it will be windier and cooler with more splashing.

In order to make progress sailing against the wind, a boat must tack back and forth across the no-sail zone. Each tack will sail the boat closer to a point in the upwind direction, but the typical close-hauled course to a point upwind looks like a zig-zag across the wind.

It's a good idea for boat owners to learn the limits of the boat for upwind sailing, and how to maximize "point" into the wind. If you have to sail somewhere upwind - and especially if you want to race - knowing how high you can sail helps you sail more efficiently.

Reaching: Fastest Point of Sail

Reaching is the point of sail between close hauled and running - from 50 degrees off the wind through about 135 degrees. But that's a very broad range, so we break reaching angles out a bit more into Close Reach, Beam Reach, and Broad Reach.

Reaching is typically the fastest point of sail, and beam reaching in particular for most boats is very quick. The angle of the wind against the boat and the keel pushing back against the water directs the most force into forward motion and can be an efficient and fun direction to sail.

Unlike beating, when you're reaching it's usually because you're headed straight for a point, and that point is not directly upwind from you. So you don't have to worry about tacking back and forth. You just need to keep the sails trimmed, and the boat pointed where you want to go.

As you bear away from the close hauled onto a reach, the ease the sails a bit more the further you head off the wind. As you speed up, the apparent wind appears to increase, but as the wind moves back, it drops more.

Close Reach: Sailing Close to the Wind

The close reach is the point of sail between close hauled (about 45 degrees) and beam reaching at 90 degrees off the wind. If you're sailing hard upwind on a beat, and you ease the sails and point the boat a bit off the wind, you are close reaching.

The wind is still forward of the boat, so you're making upwind progress on a close reach. The boat will sail faster through the water and heel a little less as you fall off the wind, but you will make less progress directly upwind as you sail further.

Beam Reach: Easiest Point of Sail

When the wind is ninety degrees off the boat, or perpendicular to the beam, you're on a beam reach. For most boats, this is the fastest point of sail since the wind hits the boat at a right angle and we can trim the sails for maximum forward motion.

To trim on a beam reach, ease each sail until it flutters a little, then tighten it in to stop the flutter. While there may be additional controls on your boat to adjust for more fine trim and better performance, for a beginning sailor, these gross sail adjustments will get you on a fast, easy reach.

There is still some heel on a beam reach, but it's much more comfortable than sailing upwind and the boat will tilt a lot less. Big breezes can still add some heel during puffs, but the boat will also dig in and sail faster when that happens!

Broad Reach: Leaving Upwind

Past beam reaching, from 90 degrees until about 135 degrees, you're sailing on a broad reach. This is also a fast point of sail, and the sails should be easy to stay full with telltales streaming. Genoa cars should also move forward, and a little outhaul ease may give you a nice little boost.

You're no longer sailing upwind, but the boat is still getting power from the sails-against-keel action. Your regular upwind sails will still draw very well and keep you powered up, though in light air some sailors will deploy special sails for better performance to capture the downwind components of wind they're in.

Running: Sailing Downwind

Running off the wind is downwind sailing, and for most boats runs about 135 degrees off the wind to 180 degrees, or Dead Down Wind (or DDW). Sailing with a jib and main combination gets very slow, and you may need to take some extra steps like holding out the jib with a pole to keep it full, or sailing wing-on-wing, with the main on one side of the boat and the jib on the other like a set of bird wings.

The alternative is to fly a spinnaker, the best way to get more speed off the wind. These large, light sails fill like parachutes and give a lot more driving force than a heavy jib or genoa, which may get blanketed behind the main or have a hard time staying full in the lighter apparent wind.

The exact angle to switch to downwind sails varies by the boat, sail type, and conditions. A symmetrical spinnaker typically isn't flown until deeper sailing angles, but a boat with an asymmetrical spinnaker on a bow sprit may sail best with that spinnaker starting on a broad reach.

When running deep, be careful of accidental jibes. Sailing DDW can be the straightest line to a point, but a sudden shift in the wind can move the wind across your stern, and suddenly your main sail is on the wrong side of the boat and may slam over in an unplanned jibe. This can damage the boat and cause serious injuries.

It's often better for less experienced sailors to sail a little higher than DDW until they know how to spot shifts. Or you can rig a preventer to hold the boom in place to stop the jibe.

Did you find the answer to your specific question?

👍 21 👎 5

Comments

Jack

HI…I’d like to ask some questions by email…can you send me yours (please) My regards Jack

Leave a comment